During the last year or so, my pupils and I have spent time exploring our daily working and studying environment, our school building. We see the architecture as we pass through it, but at the same time barely seem to notice it. We take it so much for granted of what we see on a daily basis. Taking it as a subject for drawing, painting, or photography, forces us to look at the familiar in a different and more focused way.

This ongoing project started a year ago when I began a series of drawings of my own that pictured an empty school building on dark winter mornings. The pupils and most staff were yet to arrive, corridors were empty and classrooms deserted. It was a viewpoint that throws our attention onto architecture, the forms, the materials and structure.

Parts of the school are certainly quite interesting, particularly the section built in the late 1940s. But other sections built much later, and dare I say with less attention to detail, also still have their charm. There are twisting staircases, long corridors and glass sky-bridges linking buildings.

Having completed my own set of artworks, pupils followed with their own sets of photographic interpretations and drawings inspired by our school last spring.

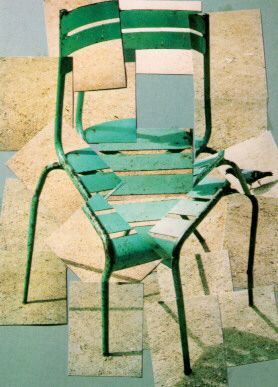

This autumn I’ve again set a group of pupils the challenge of representing the building and its spaces in a photographic project. The inspiration for this project lies very much in the photographic collages made by David Hockney in the 1970s and 1980s. These multiple photograph collages, carefully put together, but also retaining a rather chaotic appearance seemed to offer interesting possibilities for my groups of 15 year olds to explore.

The results that came in were certainly interesting. Some aspects of the architecture seemed to lend themselves particularly well to this expansive approach to photography. The hall at the front end of the school with its fantastic chessboard floor and globe lighting being a particular favourite!

For those who might be interested in the technical steps of the project, it could hardly be simpler. The basic steps:

- Take a series of 25-30 photographs, allowing each one to slightly overlap with the previous one. Encourage the pupils to stand on a single spot and turn through a full 180 degrees when taking the pictures.

- Upload the photographs onto a computer

- Open PowerPoint, and use a single slide to create the collage

- Import/insert all the photographs in one go onto the slide

- Resize the set of photographs to a size that you think will allow them all to fit on the one slide when collages come together

- Spread the photographs out around the edges of the slide

- Place a photograph that you know to be roughly central to the collage in the middle of the slide

- Start adding and overlapping other pictures and gradually build the collage outwards

My pupils have enjoyed their visits this week and once again have been quite surprised at the cultural offerings that the local museum can offer. The complexity and rich fantasy element in Berens’ work is particularly engaging in the eyes of the pupils, at least when they pause long enough in front on a single work to give themselves time to unpack some of the riches to be found there. It is no secret that patience not the strongest point of an average fifteen year old!

My pupils have enjoyed their visits this week and once again have been quite surprised at the cultural offerings that the local museum can offer. The complexity and rich fantasy element in Berens’ work is particularly engaging in the eyes of the pupils, at least when they pause long enough in front on a single work to give themselves time to unpack some of the riches to be found there. It is no secret that patience not the strongest point of an average fifteen year old!